Disadvantaged children struggle in ‘lottery of birth’

Vietnamese children born into the Kinh ethnic group were nearly three and a half times less likely to die than their non-Kinh peers, Save the Children reports.

Despite a tremendous progress Vietnam has made in reducing under-five child mortality rates over the last two decades, a new research conducted by Save the Children has found that large groups of children are still being left behind, simply because of where they live and the circumstances in which they are born.

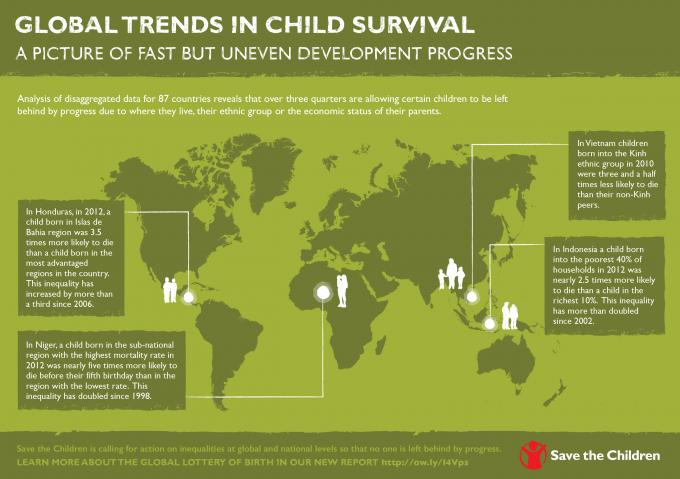

The Lottery of Birth report, based on inaugural analysis of disaggregated data from 87 low and middle income countries around the world, reveals that in more than three quarters of these countries inequalities in child survival rates are actually worsening, resulting in some groups of children making far slower progress than their better-off peers.

In Vietnam, parents from minority ethnic groups are less aware of government health programmes and informations about their conditions and treatment – an issue exacerbated by language barriers and local habits of neonatal care.

A big part in the cause of deaths for children under the age of five is due to the difficulties in access to neonatal services or the quality of neonatal services for families in remote areas. The total neonatal mortality accounts for 54% of deaths in Vietnam.

Save the Children’s analysis suggests that, without a true step change in action, the lottery of birth will continue into the future, slowing progress towards the ultimate goal of ending preventable child deaths for generations to come.

However, tackling this inequality is possible. Indeed, almost a fifth of the countries in the report, including Rwanda, Malawi, Mexico, and Bangladesh, have successfully combined rapid and inclusive reductions in child mortality, achieving faster progress than most countries, while at the same time ensuring that no groups of children are left behind.

The agency calls for the international community to commit to ending preventable child deaths by 2030.

The new development framework, which will replace the MDGs, will be agreed upon at the United Nations General Assembly in September 2015. This framework must set out ambitious child and maternal survival targets and commit to working towards universal health coverage.

It should also include targets to ensure that even the poorest, most marginalised and disadvantaged groups of children are included in global race to improve under-five child survival by 2030.

‘In this day and age, it is scandalous that so many children’s chances of survival across the world is purely a matter of whether or not they were lucky enough to be born into an affluent family who can access quality healthcare,’ says Gunnar Andersen, Save the Children in Vietnam’s Country Director.

‘We know that change is possible. We now have a significant window of opportunity to drive this change; world leaders must do everything in their power to ensure that they grasp this opportunity with both hands.’

Other key Lottery of Birth findings include:

- Disadvantaged ethnic groups and regions are most likely to be left behind; regional disparities in child mortality rates increased in 59% of the countries, while disparities between ethnic groups in 76%.

- More positively, 17,000 fewer children now die every day than they did in 1990, and the global under-five child mortality rate nearly halved from 90 to 46 deaths per 1000 live births between 1990 and 2013.

- About a fifth of countries have achieved above median reductions in child mortality over the past decade, while at the same time ensuring that no particular groups of children are left behind.

Vietnam

Vietnam